Some thoughts on ToB's GPU-based fuzzing

The blog

The blog we’re looking at today is an incredible blog by Ryan Eberhardt on the Trail of Bits blog! You should read it first, it’s really neat, there’s also some awesome graphics in it which makes it a super fun read!

Let’s build a high-performance fuzzer with GPUs!

Summary

In the ToB blog, they talk about using GPUs to fuzz. More specifically, they talk about lifting a target architecture into LLVM IR, and then emitting the LLVM IR to a binary which can run on a GPU. In this case, they’re targeting PTX assembly to run on the NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU. This is done using a tool ToB has been working on for quite a while, called remill, which is designed for binary translation. Remill alone is incredibly impressive.

The target they picked as a benchmark is the BFP packet filtering code in libpcap, pcap_filter_with_aux_data. This function is pretty simple, and it executes a compiled BPF filter and uses it to extract information and filter a packet.

The blog talks about some of the hurdles in getting performant execution on GPUs, organization of data, handing virtual memory, etc. Once again, go read it. It’s really neat, the graphics alone make it a worthwhile read!

I’m super excited about this blog, mainly because it’s very similar to vectorized emulation that I’ve worked on in the past, and it starts answering questions about GPU-based fuzzing that I have been too lazy to look into. While this blog goes into some criticisms, it’s important to note that the research is only just starting, there is much progress to be had! It’s also important to note that this research has been being done by Ryan for only 2 months. That is incredible progress.

The Problems

Nevertheless, I have a few problems with the blog that stood out to me. I’m kind of always the asshole pointing these things out, but I think there are some important things to discuss.

The comparison

In the blog, the comparison being done and being presented is largely about comparing the performance of libfuzzer, against their GPU based fuzzer. Further, the comparisons are largely about the number of executions per second (or as I call them, fuzz cases per second), per unit US dollar. This comparison is largely to emphasize the cost efficiencies of fuzzing on the GPU, so we’ll keep that in mind. We don’t want to stray too far from their actual point.

Their hardware they’re testing on are 2 different Google Cloud Compute nodes which have various specs. The one used to benchmark libfuzzer is an n1-standard-8, this is a 4 core, 8 hyperthread, Intel Skylake machine. This costs $0.38/hour according to their blog, and of course, this checks out.

The other machine they’re testing on, for their GPU metrics, is a NVIDIA Tesla T4 single GPU compute node from Google Cloud Project. They claim this costs $0.35/hour, and once again, that’s accurate. This means the two machines are effectively the same price, and we’ll be able to compare them at a rough level without really taking into consideration their costs.

In their blog, they mention that “This isn’t an entirely fair comparison.”, and this is largely referring to that their fuzzer is not providing mutated inputs to the function, whereas libfuzzer is. This is a major issue. However, their fuzzer is resetting the state of the target every fuzz case, and libfuzzer is relying on the function not having any peristant state that needs to be reset. This gives libfuzzer a large advantage. Finally, the GPU based fuzzer also works on binaries, where libfuzzer requires source, so once again, there’s a lot of variables at play here. It is important to note, they’re mainly looking for order-of-magnitude estimates. But… this is a lot more than should be controlled for in my opinion. Important to also note that the blog concludes with a ~4x improvement from libfuzzer, thus, it’s well below the order-of-magnitude concerns of unfairness.

Of course, if you’ve read my blogs before. You’ll know I absolutely hate comparisons between problems with multiple variables. First of all, the cost of mutating an input is incredibly expensive, especially for a potentially large packet, say 1500 bytes. Further, the target which is being picked is a single function which does very little processing from first glance, but we’ll look into this more later.

So, let’s start off by eliminating one variable right away. What is the cost of generating an input from libfuzzer, and what is the cost of the actual function under test. This will effectively tell us how “fair” the execution comparison is, the binary vs source is subjective and clearly the binary-based engine is more impressive.

How do we do this? Well, let’s first figure out how fast libfuzzer can execute something that does literally nothing. This will give us a baseline of libfuzzer performance given it’s targeting something that does literally nothing.

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

extern int LLVMFuzzerTestOneInput(const uint8_t *Data, size_t Size) {

return 0; // Non-zero return values are reserved for future use.

}

clang-12 -fsanitize=fuzzer -O2 test.c

We’ll run this test on a Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6252N CPU @ 2.30GHz turboing to 3.6 GHz. This isn’t the same as their GCP setup, but we’ll do some of our own comparisons locally, thus we’re talking about relatives and not absolutes.

They don’t talk much in their blog about what they used to seed libfuzzer, so we’ll just give it no seeds and cap the input size to 1500 bytes, or about a single MTU for a network packet.

pleb@grizzly:~/libpcap/harness$ ./a.out -max_len=1500

INFO: Running with entropic power schedule (0xFF, 100).

INFO: Seed: 2252408900

INFO: Loaded 1 modules (1 inline 8-bit counters): 1 [0x4ea0b0, 0x4ea0b1),

INFO: Loaded 1 PC tables (1 PCs): 1 [0x4c0840,0x4c0850),

INFO: A corpus is not provided, starting from an empty corpus

#2 INITED cov: 1 ft: 1 corp: 1/1b exec/s: 0 rss: 27Mb

#8388608 pulse cov: 1 ft: 1 corp: 1/1b lim: 1500 exec/s: 4194304 rss: 28Mb

#16777216 pulse cov: 1 ft: 1 corp: 1/1b lim: 1500 exec/s: 3355443 rss: 28Mb

#33554432 pulse cov: 1 ft: 1 corp: 1/1b lim: 1500 exec/s: 3050402 rss: 28Mb

#67108864 pulse cov: 1 ft: 1 corp: 1/1b lim: 1500 exec/s: 3195660 rss: 28Mb

#134217728 pulse cov: 1 ft: 1 corp: 1/1b lim: 1500 exec/s: 3121342 rss: 28Mb

Hmm, it seems it has settled in at about 3.12 million executions per second on a single core. Hmm, that seems a bit fast compared to the 1.9 million executions per second they see on their 8 thread machine in GCP, but maybe the target is really that complex and slows down performance.

Next, lets see how expensive the target code is outside of libfuzzer.

use std::time::Instant;

use pcap_sys::*;

#[link(name = "pcap")]

extern {

fn bpf_filter_with_aux_data(

pc: *const bpf_insn,

p: *const u8,

wirelen: u32,

buflen: u32,

aux_data: *const u8,

);

}

fn main() {

const ITERS: u64 = 100_000_000;

unsafe {

let mut program: bpf_program = std::mem::zeroed();

// Ethernet linktype + 1500 snapshot length

let pcap = pcap_open_dead(1, 1500);

assert!(!pcap.is_null());

// Compile the program

let status = pcap_compile(pcap, &mut program,

"dst host 1.2.3.4 or tcp or udp or ip or ip6 or arp or rarp or \

atalk or aarp or decnet or iso or stp or ipx\0"

.as_ptr() as *const _,

1, PCAP_NETMASK_UNKNOWN);

assert!(status == 0, "Failed to compile pcap thingy");

let buf = vec![0u8; 1500];

let time = Instant::now();

for _ in 0..ITERS {

// Filter a packet

bpf_filter_with_aux_data(

program.bf_insns,

buf.as_ptr(),

buf.len() as u32,

buf.len() as u32,

std::ptr::null()

);

}

let elapsed = time.elapsed().as_secs_f64();

print!("{:14.2} packets/second\n", ITERS as f64 / elapsed);

}

}

We’re just going to compile the filter they mention in their blog, and then call bpf_filter_with_aux_data in a loop, applying the filter, and then we’ll print the number of iterations per second that we can do. In my specific case, I’m using libpcap-1.9.1 as distributed as a source code zip, this may differ slightly from their version.

pleb@grizzly:~/libpcap/harness$ RUSTFLAGS="-L../libpcap-1.9.1" cargo run --release

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.01s

Running `target/release/harness`

18703628.46 packets/second

Uh oh, that’s a bit concerning. The target can be executed about 18.7 million times per second, however libfuzzer is capped at pretty much a maximum of 3.1 million executions a second. This means the overhead of libfuzzer, which is not part of this comparison, is a factor of about 6. This means that libfuzzer is given about a 6x penalty, compared to the GPU fuzzer, which immediately gets rid of the ~4.4x advantage that the GPU fuzzer had over libfuzzer in their blog.

This unfortunately, was exactly as I expected. For a target this small, the overhead of creating an input greatly exceeds the cost of the target execution itself. This, unfortunately, makes the comparison against libfuzzer pretty much invalid in my eyes.

Trying to make the comparison closer

I’m lucky in that I have many binary-based snapshot fuzzers sitting around. It’s kind of my specialty. It’s important to note, from this point on, this comparison is for myself. It’s not to critique the blog, it’s simply for me to explore my performance against ToB’s GPU performance. I don’t care which one is better, this is largely for me to figure out if I personally want to start investing some time and money into GPU based fuzzing.

So, to start off, I’m going to compare the GPU fuzzer against my vectorized emulation. Vectorized emulation is a technique that I use to execute multiple VMs in parallel using AVX-512. In this specific case, I’m targeting a RISC-V processor (rv64ima) which will be emulated on my Intel machines by using AVX-512. Since 512 bits / 64 bits is 8, that means I’m running 8 VMs per hardware thread.

Vectorized emulation entirely contains only my own code. I wrote the lifters, the IL, the optimization passes, the JITs, the assemblers, the APIs, everything. This gives me a massive amount of control over adapting it to various targets, and make rapid changes to internals when needed. But, it also means, my code generation should be significantly worse than something like LLVM, as I do only the most basic optimizations (DCE, deduplication, etc). I don’t do any reordering, loop unrolling, memory access elision, etc.

Let’s try it!

The environment

To try to get as close to comparing against ToB’s GPU fuzzer, I’m going to fuzz a binary target and provide no mutation of the inputs. I’m simply going to use a 1500-byte buffer containing zeros. Unfortunately, there’s no specifics about what they used as an input, so we’re making the assumption that a 1500-byte zeroed out input and simply invoking bpf_filter_with_aux_data, waiting for it to return, then resetting VM memory back to the original state and running again is fair. Due to how many or conditions are used in the filter, and given the packet doesn’t match any, should mean we’re seeing the worst case performance (eg. evaluating all expressions). I’m not perfectly familiar with BPF filtering, but I’d imagine there’s an early exit on a match, and thus if the destination was 1.2.3.4, I’d suspect the performance would be improved. Without this being clarified from the ToB blog, we’re just going with worst case (unless I’m incorrect in my understanding of BPF filters, maybe there’s no early exit).

Anyways, the target code that I’m using is as such:

use std::time::Instant;

use pcap_sys::*;

#[link(name = "pcap")]

extern {

fn bpf_filter_with_aux_data(

pc: *const bpf_insn,

p: *const u8,

wirelen: u32,

buflen: u32,

aux_data: *const u8,

);

}

#[no_mangle]

pub extern fn fuzz_external() {

const ITERS: u64 = 1;

unsafe {

let mut program: bpf_program = std::mem::zeroed();

// Ethernet linktype + 1500 snapshot length

let pcap = pcap_open_dead(1, 1500);

assert!(!pcap.is_null());

// Compile the program

let status = pcap_compile(pcap, &mut program,

"dst host 1.2.3.4 or tcp or udp or ip or ip6 or arp or rarp or \

atalk or aarp or decnet or iso or stp or ipx\0"

.as_ptr() as *const _,

1, PCAP_NETMASK_UNKNOWN);

assert!(status == 0, "Failed to compile pcap thingy");

let buf = vec![0x41u8; 1500];

// Filter a packet

bpf_filter_with_aux_data(

program.bf_insns,

buf.as_ptr(),

buf.len() as u32,

buf.len() as u32,

std::ptr::null()

);

}

}

fn main() {

fuzz_external();

}

This is effectively the same as above, but it no longer loops. But, since I’m using a binary-based snapshot fuzzer, and so are they, we’re going to actually snapshot it. So, instead of running this entire program every fuzz case, I’m going to put a breakpoint on the first instruction of bpf_filter_with_aux_data, and run the RISC-V JIT until it hits it. Once it hits that breakpoint, I will make a snapshot of the memory state, and at that point I will create threads which will work on executing it in a loop.

Further, I will add another breakpoint on the return site of bpf_filter_with_aux_data to immediately terminate the fuzz case upon return. This avoids having the program do cleanup (like freeing buf), and otherwise bubbling up to an exit() syscall. Their blog isn’t super clear about this, but from their wording, I suspect this is a pretty similar setup. Effectively, only bpf_filter_with_aux_data is executing, and once it is not, the VM is reset and run again.

My emulator has many different operating modes. I have different coverage levels (covering blocks, covering PCs, etc), different levels of memory protection (eg. byte-level permissions which cause every byte to have its own permissions), uninitialized memory tracking (accessing allocated memory and stacks is invalid unless it has been written to first), as well as register taint tracking (logging when user input affected register state for both register reads and writes).

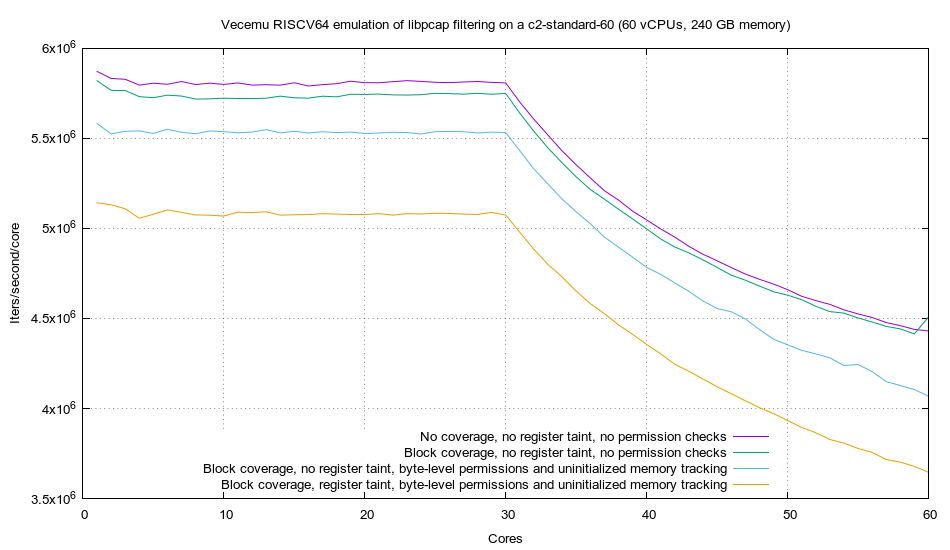

Since many of these vary in performance, I’ve set up a few tests with a few common configurations. Further, I’ve provisioned a 60 core c2-standard-60 (30 Cascade Lake Intel cores, totalling 60 hyper-threads) machine from Google Cloud Project to try to apples-to-apples as best I can. This machine costs $3.1321/hour, and thus, we’ll have to divide by these costs to make it fair when we do dollar-based comparisons.

Here… we… go!

Okay cool, so what is this graph telling us? Well, it’s showing us the number of iterations per second per core on the Y axis, against the number of cores being used on the X axis. This is not just telling me the overall performance, but also the scaling performance of the fuzzer, or how well it uses cores.

We’re going to ignore all lines other than the top line, the one in purple (blue?). We see that the line is relatively flat until 30 cores, then it starts falling off. This is great! This lines up with ideally what we want. The emulator is scaling linearly as cores are added, until we start getting past 30 cores, where they become hyperthreads and they’re not actually physical cores. The fact that the line is flat until 30 cores makes me very happy, and a lot of painstaking engineering went into making that work!

Anyways, we have multiple lines here. The top line, to no surprise, is gathering no coverage information, isn’t tracking taint, nor is it checking permissions. Of course it’s the fastest. The next line, in green, only adds block-level code coverage. It’s almost no performance hit, and nor would I expect it to be. The JIT self-modifies once coverage has been reported, and thus the only cost is a bit of icache pollution due to some nopped out code being jumped over.

Next, we have the light blue line, which at this stage, is the first line that actually matters. This one adds checking of permissions, as well as uninitialized memory tracking. This is done at a byte-level, and thus behaves very similarly to ASAN (in fact, it allows arbitrary byte-sized holes in memory, where ASAN can only mark trailing bytes as inaccessible). This of course, has a performance cost. And this is the real line, there’s no way I’d ever run a fuzzer without permission checks as the target would simply crash the host. I could use a more relaxed permission checking model (like using the hardware MMU on Intel to provide 512-byte-level permissions (4096-byte pages / 8 VMs interleaved per page)), and I’d have the green line in performance, but it’s not worth it. Byte level is too important to me.

Finally, we have the orange line. This one adds register “taint” tracking. This effectively horizontally looks at neighboring VMs during execution to determine if one VM has written or read a different value to a register. This allows me to observe and feed back information about which register values are influenced by the user input, and thus is important information for cutting down on mutation wastes. That being said, we’re not mutating, so it doesn’t really matter, we’re just looking at the runtime costs of this instrumentation.

Where does this leave us? Well, we see that on the 60 core machine, with the light blue line (the one we care about), we end up getting about 4.1 million iterations per second per core. Since we’re running 60 cores (technically 60 threads) at this rate, we can just multiply to see that we’re getting about 250 million iterations per second on this 60 core c2-standard-60 machine.

Well, this is the number we want. What does this come out to for iterations/second/$? Simply divide 250 million by $3.1321/hour, and we get about 79.8 million iters/second/dollar/hour.

I don’t have access to their GPU code so I can’t reproduce it, but their number they claim is 8.4M iterations/second on the $0.35/hour GPU, and thus, 23.9 million iters/second/dollar/hour.

This gives vectorized emulation about a 3x advantage for performance per dollar compared to the GPU based compute. It’s important to note, both technologies have some pretty large improvements to performance which may be possible. I suspect with some optimization both could probably see 2-3x improvements, but at that point they start hitting some very real hardware limitations in performance.

Where does this leave us?

I have some suspicions that GPUs will struggle with low latency memory accesses, especially when so many VMs are diverging and doing different things. These benchmarks are best case for both these technologies, as the inputs aren’t affecting execution flow, and the memory utilization is quite low.

GPUs have some major memory limitations, that I think make them impractical for fuzzing. As mentioned in the ToB blog, a 16 GiB GPU running 40,000 threads only has 419 KiB per thread available for storage. This means the corpuses, coverage databases, and all modified memory by a fuzz case must be below 419 KiB. This unfortunately isn’t a very practical limit. Right now I’m doing some freetype2 fuzzing in light of the Google Project Zero CVE-2020-15999, and I’m pusing 50 GiB of memory use for the 1,536 VMs I run. Vecemu does memory deduplication and CoW for all memory, and thus my memory use is quite low. Ultimately, there are user-controlled allocations that occur and re-claiming the memory every fuzz case doesn’t prove very feasible. This is also a tiny target, I fuzz many targets where the input alone exceeds 1 MiB, let alone other memory used by the target.

Nevertheless, I think these problems may be solvable with creative use of transferring memory in blocks, or maybe chunking fuzz cases into sections which use less than 400 KiB at a time, or maybe just reduce the number of threads. There’s definitely solutions here, and I definitely don’t doubt that it’s possible, but I do wonder if the overheads and complexities beat what can be done directly on the CPU with massive caches and access to all memory at a relatively low cost (as opposed to GPU<->CPU memory access).

Is there more perf?

It’s important to note that my vectorized emulation is not running faster than native execution. I’m still emulating RISC-V and applying some really strict memory permission checks that slow things down, this makes my memory accesses really expensive. I am happy to see though, that vectorized emulation looks to be within about ~3x of native execution (18M packets/second in our native libpcap harness mentioned early on, 5.5M with ours). This is pretty crazy, given we’re working with binaries and applying byte-level permissions to a target which isn’t even supported by ASAN! How cool is that!?

Vectorized emulation runs close to or faster than native execution when the target has few memory loads and stores. This is by far the bottleneck (~80%+ of CPU time is spent doing my memory translations). Doing some optimization passes to reduce memory loads and stores in my IL would probably allow me to realize some of these gains.

Since I’m not running at native speeds, we know that this isn’t as fast as could be done by just building libpcap for x86 and running it. Of course this requires source, but we know that we can get about a 3x speedup by fuzzing it natively. Thus, if I have a 3x improvement on the GPU fuzzing cost effectiveness, and there’s a 3x speedup from my emulation to just “running it natively on x86”, then there’s a 9x improvement from GPU execution to just run it natively.

This kinda… proves my earlier point. The benchmark is not comparing libfuzzer to the GPU fuzzer, it’s comparing the GPU fuzzer running a target, compared to libfuzzer performing orchistration of a fuzzer and mutations. It’s just… not really comparing anything valuable. But of course, like I always complain about, public fuzzer performance is often not great. There are improvements we can get to our fuzzing harnesses, and as always, I implore people to explore the powers of in-memory, snapshot based fuzzing! Every time you do IPC, update an atomic, update/check a database, do an allocation, etc, you lose a lot of performance (when running at these speeds). For example, in vectorized emulation for this very blog, I had to batch my fuzz case increments to only happen a few times a second. Having all threads updating an atomic ~250M times a second resulted in about a 60% overall slowdown of the entire harness. When doing super tight loop fuzzing like this (as uncommon as it may be), the way we write fuzzing harnesses just doesn’t work.

But wait… what even are these dollar amounts?

So, it seems that vectorized emulation is only slightly faster than the GPU results (~3x). Vectorized emulation also has years of research into it, and the GPU research is fairly new. This 3x advantage is honestly not a big deal, it’s below the noise floor of what really matters when it comes to accessibility of hardware. If you can get GPUs or GPU developers easier than AVX-512 CPUs and developers, the 3x difference isn’t going to make a difference.

But we have to ask, why are we comparing dollar amounts? The dollar amounts are largely to determine what is most cost effective, that makes sense. But… something doesn’t seem right here.

The GPU they are using is an NVIDIA Tesla T4 and costs $0.35/hour on Google Cloud Project. The CPU they are using (for libfuzzer) is a quad core Skylake which costs $0.38/hour, or almost 10% more. What? An NVIDIA Tesla T4 is $2,152 (cheapest price I could find), and a quad core Skylake is $150. What the?

Once again, I hate the cloud. It’s a pretty big ripoff for long-running compute, but of course, it can save you IT costs and allow you to dynamically spin up.

But, for funsies, let’s check the performance per dollar for people who actually buy their hardware rather than use cloud compute.

For these benchmarks I’m going to use my own server that I host in my house and purchased for fuzzing. It’s a quad socket Xeon 6252N, which means that in total it has 96 cores and 192 threads, clocking at 2.3 GHz base, turboing to 3.6 GHz. The MSRP (and price I paid) for these processors is $1788. Thus, ~$7,152 for just the processors. Throw in about $2k for a server-grade chassis + motherboard + power supplies, and then ~$5k for 768 GiB of RAM, and you get to the $14-15k mark that I paid for this server. But, we’ll simplify it a bit, we don’t need 768 GiB of RAM for our example, so we’ll figure out what we want in GPUs.

For GPUs, the Tesla T4s are $2,152 per GPU, and have 16 GiB of RAM each. Lets just ignore all the PCI slotting, motherboards, and CPU required for a machine to host them, and we’ll just say we build the cheapest possible chassis, motherboard, PSU, and CPUs, and somehow can socket these in a $1k server. My server is about $9k just for the 4 CPUs + $2k in chassis and motherboards, and thus that leaves us with $8k budget for GPUs. Lets just say we buy 4 Tesla T4s and throw them in the $1k server, and we got them for $2k each. Okay, we have a 4 Tesla T4 machine and a 4 socket Xeon 6252N server for about $9k. We’re fudging some of the numbers to give the GPUs an advantage since a $1k chassis is cheap, so we’ll just say we threw 64 GiB into the server to match the GPUs ram and call it “even”.

Okay, so we have 2 theoretical systems. One with 96C/192T of Xeon 6252Ns and 64 GiB RAM, and one with 4 Tesla T4s with 64 GiB VRAM. They’re about $9k-$11k depending on what deals you can get, so we’ll say each one was $9k.

Well, how does it stack up?

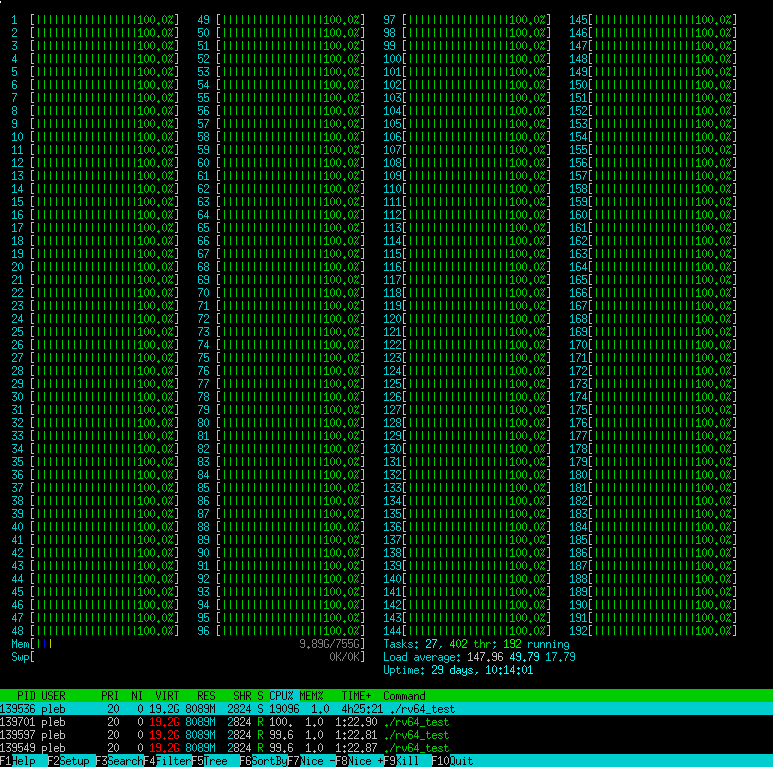

I have the 4x 6252N system, so we’ll run vectorized emulation in “light blue” line mode (block coverage, byte-level permissions, uninitialized mem tracking, and no register taint tracking), this is a common mode for when I’m not fuzzing too deep on a target. Well, lets light up those cores.

Sweet, we’re under 10 GiB of memory usage for the whole system, so we’re not really cheating by skimping on the memory in our theoretical 64 GiB build.

Well, we’re getting about 700 million fuzz cases per second on the whole system. Woo! That’s a shitton! That is 77k iters/second/$. Obviously this seems “lower” than what we saw before, but this is the iters/second for a one time dollar investment, not a per-hour cloud fee.

So… what do we get on the GPU? Well, they concluded with getting 8.4 million iters/sec on the cloud compute GPU. Assuming it’s close to the performance you get on bare metal (since they picked the non-preemptable GPU option), we can just multiply this number by 4 to get the iters/sec on this theoretical machine. We get 33.6 million iterations per second total, if we had 4 GPUs (assuming linear scaling and stuff, which I think is totally fair). Well… that’s 3,733 iters/second/$… or about 21x more expensive than vectorized emulation.

What gives? Well, the CPUs will definitely use more power, at 150W each you’ll be pushing 600W minimum, but I observe more in the ballpark of 1kW when running this server, when including peripherals and others. The Tesla T4 is 70W each, totalling 280W. This would likely be in a system which would be about 200W to run the CPU, chassis, RAM, etc, so lets say 500W. Well, it’d be about 1/2 the wattage of the CPU-based solution. Given power is pretty cheap (especially in the US), this difference isn’t too major, for me, I pay $0.10/kWh, thus the CPU server would cost about $0.20 per hour, and the GPU build would cost about $0.10 per hour (doubled for cooling). These are my “cloud compute” runtime costs, and thus the GPUs are still about 10x more expensive to run than the CPU solution.

Conclusion

As I’ve mentioned, this GPU based fuzzing stuff is incredibly cool. I can’t wait to see more. Unfortunately, some of the methodologies of the comparison aren’t very fair and thus I think the claims aren’t very compelling. It doesn’t mean the work isn’t thrilling, amazing, and incredibly hard, it just means it’s not really time yet to drop what we’re doing to invest in GPUs for fuzzing.

There’s a pretty large discrepency in the cost effectiveness of GPUs in the cloud, and this blog ends up getting a pretty large advantage over libfuzzer for something that is really just a pricing decision by the cloud providers. When purchasing your own gear, the GPUs are about 10x more expensive than the CPUs that were used in the blogs tests (quad-core Skylake @ $200 or so vs a NVIDIA T4 @ $2000). The cloud prices do not reflect this difference, and in the cloud, these two solutions are the same price. That being said, those are real gains. If GPUs are that much more cost effective in the cloud, then we should definitely try to use them!

Ultimately, when buying the hardware, the GPU solution is about 20x less cost effective than a CPU based solution (vectorized emulation). But even then, vectorized emulation is an emulator, and slower than native execution by a factor of 3, thus, compared to a carefully crafted, low-overhead fuzzer, the GPU solution is actually about 60x less cost effective.

But! The GPU solution (as well as vectorized emulation) allow for running closed-source binary targets in a highly efficient way, and that definitely is worth a performance loss. I’d rather be able to fuzz something at a 10x slowdown, than not being able to fuzz it at all (eg. needing source)!

Hats off to everyone at Trail of Bits who worked on this. This is incredibly cool research. I hope this blog didn’t come off as harsh, it’s mainly just me recording my thoughts as I’m always chasing the best solution for fuzzing! If that means I throw away vecemu to do GPU-based fuzzing, I will do it in a heartbeat. But, that decision is a heavy one, as I would need to invest thousands of hours in GPU development and retool my whole server room! These decisions are hard for me to make, and thus, I have to be very critical of all the evidence.

I can’t wait to see more research from you all! This is incredible. You’re giving me a real run for my money, and in only 2 months of work, fucking amazing! See you soon!

Random opinions

I’ve been asked a few things about my opinion on the GPU-based fuzzing, I’ll answer them here.

Is not having syscalls a problem?

No. It’s not. It is for people who want to use the tool. But this is a research tool and is for exploring what is possible, the act of fuzzing on a GPU by running binary translated code is incredible, that’s the focus here! GPUs are turing complete, we can definitely emulate syscalls on them if needed. It might be a lot of work, a lot of plumbing, maybe a perf hit, but it doesn’t stop it from being possible. Most of my fuzzers rely on emulating syscalls.

There’s also nothing preventing GPUs from being used to emulate an whole OS. You’d have to handle self-modifying code and virtual memory, which can get very expensive in an emulator, but with making software TLBs these things can be manageable to a level it’s still worth doing!

Social

I’ve been streaming a lot more regularly on my Twitch! I’ve developed hypervisors for fuzzing, mutators, emulators, and just done a lot of fun fuzzing work on stream. Come on by!

Follow me at @gamozolabs on Twitter if you want notifications when new blogs come up. I often will post data and graphs from data as it comes in and I learn!