Vectorized Emulation: MMU Design

New vectorized emulator codenamed softserve

Tweeter

Follow me at @gamozolabs on Twitter if you want notifications when new blogs come up.

Check out the intro

This is the continuation of a multipart series. See the introduction post here

This post assumes you’ve read the intro and doesn’t explain some of the basics of the vectorized emulation concept. Go read it if you haven’t!

Further this blog is a lot more technical than the introduction. This is meant to go deep enough to clear up most/all potential questions about the MMU. It expects that you have a general knowledge of page tables and virtual addressing models. Hopefully we do a decent job explaining these things such that it’s not a hard requirement!

The code

This blog explains the intent behind a pretty complex MMU design. The code that this blog references can be found here. I have no plans to open source the vectorized emulator and this MMU is just a snapshot of what this blog is explaining. I have no intent to update this code as I change my MMU model. Further this code is not buildable as I’m not open sourcing my assembler, however I assume the syntax is pretty obvious and can be read as pseudocode.

By sharing this code I can talk at a higher level and allow the nitty-gritty details to be explained by the actual implementation.

It’s also important to note that this code is not being used in production yet. It’s got room for micro-optimizations and polish. At least it should be doing the correct operations and hopefully the tests are verifying this. Right now I’m trying to keep it simple to make sure it’s correct and then polish it later using this version as reference.

Intro

Today we’re going to talk about the internals of the memory management unit (MMU) design I have used in my vectorized emulator. The MMU is responsible for creating the fake memory environment of the VMs that run under the emulator. Further the MMU design used here also is designed to catch bugs as early as possible. To do this we implement what I call a “byte-level MMU”, where each byte has it’s own permission bits. Since vectorized emulation is meant for fuzzing it’s also important that the memory state can quickly be restored to the original state quickly so a new fuzz iteration can be started.

During this blog we introduce a few big concepts:

- Differential restores

- Byte-level permissions

- Read-after-write memory (uninitialized memory tracking)

- Gage fuzzing

- Aliased/CoW memory

- Deduplicated memory

- Technical details about the IL relevant to the MMU

- Painful details about everything

Since this emulator design is meant to run multiple architectures and programs in different environments, it’s critical the MMU design supports a superset of the features of all the programs I may run. For example, system processes typically are run in the high memory ranges 0xffff... and above. Part of the design here is to make sure that a full guest address space can be used, including high memory addresses. Things like x86_64 have 48-bit address spaces, where things like ARM64 have 49-bit address spaces (2 separate 48-bit address spaces). Thus to run an ARM64 target on x86 I need to provide more bits than actually present. Luckily most systems use this address space sparsely, so by using different data structures we can support emulating these targets with ease.

The problem

Before we get into describing the solution, let’s address what the problem is in the first place!

When creating an emulator it’s important to create isolation between the emulated guest and the actual system. For example if the guest accesses memory, it’s important that it can only access it’s own memory, and it isn’t overwriting the emulator’s memory itself. To do this there are multiple traditional solutions:

- Restrict the address space of the guest such that it can fit entirely in the emulator’s address space

- Use a data structure to emulate a sparse guest’s memory space

- Create a new process/VM with only the guest’s memory mapped in

The first solution is the simplest, fastest, but also the least portable. It typically consists of allocating a buffer the size of the guest’s address space, and then any guest memory accesses are added to the base of this buffer and ensured to not go out of bounds. A model like this can rely on the hardware’s permission checking by setting permissions via mmap or VirtualProtect. This is an extremely fast model and allows for running applications that fit inside of the emulator’s address space. When running a 64-bit VM this can become tough as most OSes do not provide a means of allocating memory in the high part of the address space 0xffff... and beyond. This memory is typically reserved for the kernel. This is the model used by things like qemu-user as it is super fast and works great for well-behaving userland applications. By setting the QEMU_GUEST_BASE environment variable you can change this base and set the size with QEMU_RESERVED_VA.

The second solution is fairly slow, but allows for more strict memory permissions than the host system allows. Typically the data structure used to access the guest’s memory is similar to traditional page table models used in hardware. However since it’s implemented in software it’s possible to change these page tables to contain any metadata or sizes as desired. This is the model I ultimately use, but with a few twists from traditional page tables.

The third solution leverages something like VT-x or a thin process to almost directly use the target hardware’s page table models for a VM. This will make the emulator tied to an architecture, might require a driver, and like the first solution, doesn’t allow for stricter memory models. This is actually one of the first models I used in my emulator and I’ll go into it a bit more in the history section

History

Feel free to skip this section if you don’t care about context

To give some background on how we ended up where we ended up it’s important to go through the background of the MMU designs used in the past. Note that the generations aren’t the same MMU improving, it’s just different MMUs I’ve designed over time.

First generation

The first generation of my MMU was a simple modification to QEMU to allow for quick tracking of which memory was modified. In this case my target was a system level target so I was not using qemu-user, but rather qemu-system. I ripped out the core physical memory manager in QEMU and replaced it with my own that effectively mimicked the x86 page table model. I was most comfortable with the x86 page table model and since it was implemented in hardware I assumed it was probably well engineered. The only interest I had in this first MMU was to quickly gather which memory was modified so I could restore only the dirtied memory to save time during reset time. This had a huge improvement for my hypervisor so it was natural for me to just copy it over the QEMU so I could get the same benefits.

Second generation

While still continuing on QEMU modifications I started to get a bit more creative. Since I was handling all the physical memory accesses directly in software, there was no reason I couldn’t use page tables of my own shape. I switched to using a page table that supported 32-bit addresses (my target was MIPS32 and ARM32) using 8-bits per table. This gave me 256-byte pages rather than traditional 4-KiB x86 pages and allowed me to reset more specific dirty pages and reduces the overall work for resets.

Third generation

At this point I was tinkering around with different page table shapes to find which worked fast. But then I realized I could set the final translation page size to 1-byte and I would be able to apply permissions to any arbitrary location in memory. Since memory of the target system was still using 4-KiB pages I wasn’t able to apply byte-level permissions in the snapshotted target, however I was able to apply byte-level permissions to memory returned from hooked functions like malloc(). By setting permissions directly to the size actually requested by malloc() we could find 1-byte out-of-bounds memory accesses. This ended up finding a bug which was only slightly out-of-bounds (1 or 2 bytes), and since this was now a crash it was prioritized for use in future fuzz cases. This prioritization (or feedback) eventually ended up with the out-of-bounds growing to hundreds of bytes, which would crash even on an actual system.

Fourth generation

I ended up designing my own emulator for MIPS32, performance wasn’t really the focus. I basically copied the model I used for the 3rd generation. I also kept the 1-byte paging as by this point it was a potent tool in my toolbag. However once I switched this emulator to use JIT I started to run into some performance issues. This caused me to drop the emulated page tables and byte level permissions and switch to a direct-memory-access model.

At this time I was doing most of my development for my emulator to run directly on my OS. Since my OS didn’t follow any traditional models this allowed me to create a user-land application with almost any address space as I wanted. I directly used the MMU of the hardware to support running my JIT in the context of a different address space. In this model the JITted code just directly accessed memory, which except for a few pages in the address space, was just the exact same as the actual guest’s address space.

For example if the guest wanted to access address 0x13370000, it would just directly dereference the memory at 0x1337000. No translation, not base applied, simple.

You can see this code in the srcs/emu folder in falkervisor.

I used this model for a long time as it was ideal for performance and didn’t really restrict the guest from any unique address space shapes. I used this memory model in my vectorized emulator for quite a while as well, but with a scale applied to the address as I interleaved multiple VM’s memory.

Fifth generation

The vectorized emulator was initially designed for hard targets, and the primary goal was to extract as much information as possible from the code under test. When trying to improve it’s ability to find bugs I remembered that in the past I had done a byte-level MMU with much success. I had a silly idea of how I could handle these permission checks. Since in the JIT I control what code is run when doing a read or write, I could simply JIT code to do the permission checks. I decided that I would simply have 1 extra byte for every byte of the target. This byte would be all of the permissions for the corresponding byte in the memory map (read, write, and/or execute).

Since now I needed to have 2 memory regions for this, I started to switch from using my OS and the stripped down user-land process address space to using 2 linear mappings in my process. Since this was more portable I decided to start developing my vectorized emulator to run on just Windows/Linux. On a guest memory access I would simply bounds check the address to make sure it’s in a certain range, and then add the address to the base/permission allocations. This is similar to what qemu-user does but with a permission region as well. The JIT would check these permissions by reading the permissions memory first and checking for the corresponding bits.

Sixth generation

The performance of the fifth generation MMU was pretty good for JIT, but was terrible for process start times. I would end up reserving multiple terabytes of memory for the guest address spaces. This made it take a long time to start up processes and even tear them down as they blocked until the OS cleaned up their resources. Further commit memory usage was quite high as I would commit entire 4-KiB guest pages, which were actually 128-KiB (16 vectorized VMs * 2 regions (permission and memory region) * 4 KiB). To mitigate these issues we ended up at the current design….

Page Tables

Before we hop into soft MMU design it’s important to understand what I mean when I say page tables. Page tables take some bit-slice of the address to be translated and use it as the index for an element in a first level table. This table points to another table which is then indexed by a different bit-slice of the same address. This may continue for however many levels are used in the page table. In my case the shape of this page table is dynamically configurable and we’ll go into that a bit more.

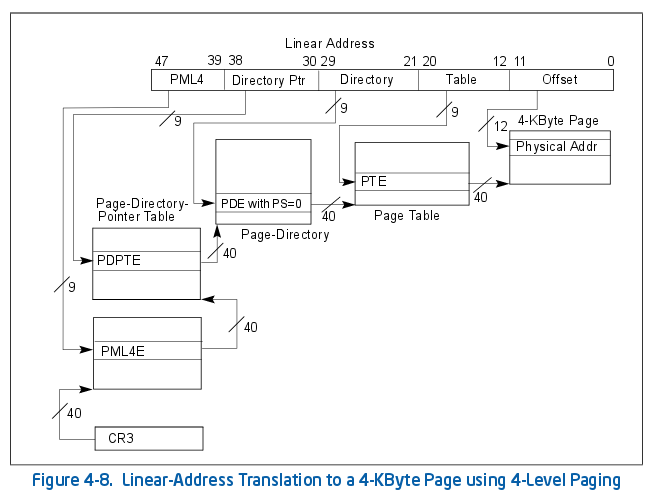

In the case of 64-bit x86 there is a 4 level lookup, where 9 bits are used for each level. This means each page table contains 512 entries. Each entry is a pointer to the next page table, or the actual page if it’s the final level. Finally the bottom 12 bits of the address are used as the offset into the page to find the specific byte. This paging model would show up as [9, 9, 9, 9, 12] according to my dynamic paging model. This syntax will be explained later.

For x86 there are alignment requirements for the page table entries (must be 4-KiB aligned). Further physical addresses are only 52-bits. This leaves 12 bits at the bottom of the page table entry and 12 bits at the top for use as metadata. x86 uses this to store information such as: If the page is present, writable, privileged, caching behavior, whether it’s been accessed/modified, whether it’s executable, etc. This metadata has no cost in hardware but in software, traversing this has a cost as the metadata must be masked off for the pointer to be extracted. This might not seem to matter but when doing billions of translations a second, the extra masking operations add up.

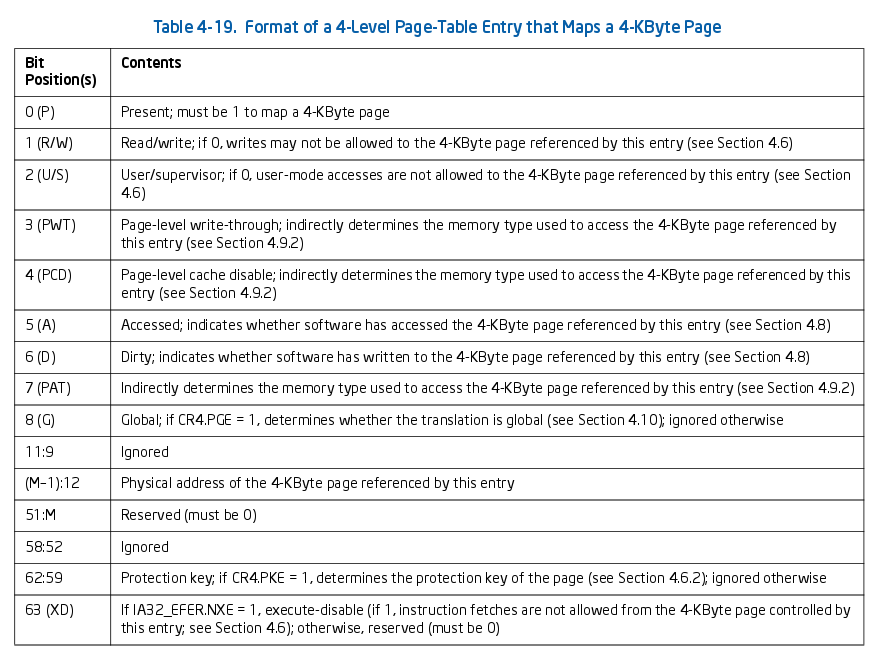

Here’s the actual metadata of a 4 KiB page on 64-bit Intel:

The overall design

My vectorized emulator is being rewritten to be 64-bit rather than 32-bit. We’re now running 2048 VMs rather than 4096 VMs as we can only run 8 VMs per thread. All of this design is for 64-bits.

When designing the new MMU there were a few critical features it needed:

- Byte level permissions

- Fast snapshot/restore times

- A data structure that could be quickly traversed in JIT

- Quick process start times

- The ability to handle full 64-bit address spaces

- Low memory usage (we need to run 2048 VMs)

- Quick methods for injecting fuzz inputs (we need a way to get fuzz inputs in to the memory millions of times per second)

- Must be easily tested for correctness

- Ability to track uninitialized memory at a byte-level

- Read-only memory shared between all cores

Applying byte-level permissions

So we have this byte-level permission goal, but how do we actually get byte-level information to apply anyways?

Since most fuzzing is done from an already-existing snapshot from a real system with 4 KiB paging and permissions, we cannot just magically get byte-level permissions. We have to find locations that can be restricted to specific byte-level sizes.

The easiest way to do this is just ignore everything in the snapshot. We can apply byte-level permissions to only new memory allocations that we emulate by adding breakpoints to the target’s allocate routines. Further by hooking frees we can delete the mappings and catch use-after-frees.

We can get a bit more fancy if we’re enlightened as to the internals of the allocator of the target under test. Upon loading of the snapshot we could walk the heap metadata and trim down allocations to the byte-level sizes they originally requested. If the heap does not provide the requested size then this is not possible. Further allocations which fit perfectly in a bin might not have any room after them to place even a single guard byte.

To remedy these problems there a few solutions. We can use page heap in the application we’re taking a snapshot in, which will always ensure we have a page after the allocation we can play with for guard bytes. Further page heap has the requested size in the metadata so we can get perfect byte-level applied.

If page heap is not available for the allocator you’re gonna have to get really creative and probably replace the allocator. You could also hack it up and use a debugger to always add a few bytes to each allocation (ensuring room for guard bytes), while logging the requested sizes. This information could then be used to create a perfect byte heap.

Getting even fancier

When going at a really hard target you could also start to add guard bytes between padding fields of structures (using symbol information or compiler plugins) and globals. The more you restrict, the more you can detect.

Design features

Basics of the vectorized model

This was covered in the intro, but since it’s directly applicable to the MMU it’s important to mention here.

Memory between the different lanes on a given core is interleaved at the 8-byte level (4-byte level for 32-bit VMs). This means that when accessing the same address on all VMs we’re able to dispatch a single read at one address to load all 8 VM’s memory. This has the downside of unaligned memory accesses being much more expensive as they now require multiple loads. However the common case most memory is accessed at the same address, and memory does not straddle a 8-byte boundary. It’s worth it.

For reference the cost of a single load instruction vmovdqa64 is about 4-5 cycles, where a vpgatherqq load is 20-30 cycles. Unless memory is so frequently accessed from different addresses and straddling 8-byte boundaries it is always worth interleaving.

VM interleaving looks as follows:

chart simplified to show 4 lanes instead of 8

| Guest Address | Host Address | Qword 1 | Qword 2 | Qword 3 | … | Qword 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x0000 | 0x0000 | 1 | 2 | 3 | … | 33 |

| 0x0008 | 0x0040 | 32 | 74 | 55 | … | 45 |

| 0x0010 | 0x0080 | 24 | 24 | 24 | … | 24 |

This interleaves all the memory between the VMs at an 8-byte level. If a memory access straddles an 8-byte value things get quite slow but this is a rare case and we’re not too concerned about it.

How do we build a testable model?

To start off development it was important to build a good foundation that could be easily tested. To do this I tried to write everything as naive as possible to decrease the chance of mistakes. Since performance is only really required in the JIT, the Rust-level MMU routines were written cleanly and used as the reference implementation to test against. If high-performance methods were needing for modifying memory or permissions they would be supplemental and verified against the naive implementation. This set us up to be in good shape for testing!

64-bit address spaces

To support full 64-bit address spaces we are forced to use some data structure to handle memory as nothing in x86 can directly use a 64-bit address space. Page tables continue to be the design we go with here.

Since we were writing the code in a naive way, it was easy to make most of the MMU model configurable by constants in the code. For example the shape of the page tables is defined by a constant called PAGE_TABLE_LAYOUT. This is used in reality in the form: const PAGE_TABLE_LAYOUT: [u32; PAGE_TABLE_DEPTH] = [16, 16, 16, 13, 3];.

This array defines the number of bits used for translating each level in the page table, and PAGE_TABLE_DEPTH sets the number of levels in the page table. In the example above this shows that we use the top 16-bits for the first level as the index, the next 16-bits for the next level, the next 16-bits again for another level, a 13-bit level, and finally a 3-bit page size. As long as this PAGE_TABLE_LAYOUT adds up to 64-bits, contains at least 2 entries (1 level page table), and at least has a final translation size of 8-byte (like in the example), the MMU and JITs will be updated. This allows profiling to be done of a specific target and modify the page table to whatever shape works best. This also allows for changes between performance and memory usage if needed.

Fast restores

When writing my hypervisor I walked the SVM page tables looking for dirty pages to restore. On x86 there are only dirty bits on the last level of the page tables. For all other levels there’s only an ‘accessed’ bit (updated when the translation is used for any access). I would walk every entry in each page table, if it was accessed I would recurse to the next level, otherwise skip it, at the final level I would check for the dirty bit and only restore the memory if it was marked as dirty. This meant I walked the page tables for all the memory that was ever used, but only restored dirty memory. Walking the page tables caused quite a bit of cache pollution which would cause significant damage to the performance of other cores.

To speed this up I could potentially place a dirty bit on every page table level, and then I would only ever start walking a path that contains a dirty page. I used this model at some point historically, however I’ve got a better model now.

Instead of walking page tables I just now append the address to a vector when I first set a dirty bit. This means when resetting a VM I only read a linear array of addresses to restore. I still need a dirty bit somewhere so I make sure I don’t add duplicates to this list. Since I no longer need to walk page tables I only put dirty bits on the final level. This was a decision driven by actual data on real targets, it’s much faster.

If during execution I run out of entries in this dirty list I exit out of the VM with a special VM-exit status indicating this list is full. This then allows me to append this list at Rust-level to a dynamically sized allocation. Since the size of this list is tunable it would grow as needed and converge to never hitting VM-exits due to dirty list exhaustion. Further this dirty list is typically pretty tiny so the cost isn’t that high.

Interestingly Intel introduced (not sure if it’s in silicon yet) a way of getting a similar thing for VMs (this is called Page Modification Logging). The processor itself will give you a linear list of dirty pages. We do not use this as it is not supported in the processor we are using.

Permissions

On classic x86 (and really any other architecture) permissions bits are added at each level of the page table. This allows for the processor to abort a page table walk early, and also allows OSes to change permissions for large regions of memory by updating a single entry. However since we’re running multiple VM’s at the same time it’s possible each VM has different memory mapped in. To handle this we need a permission byte for each byte for each VM.

Since we can’t handle the permissions checks during the page table walk (technically could be possible if the permissions are a superset of all the VM’s permissions), we get to have a metadata-less page table walk until the final level where we store the dirty bit. This means that during a page table walk we do not need to mask off bits, we can just directly keep dereferencing.

There are currently 4 permission bits. A read bit, a write bit, an execute bit, and a RaW bit (see next section). All of these bits are completely independent. This allows for arbitrary permission sets like write-only memory, and execute-only memory.

In some older versions of my MMU I had a page table for both permissions and data. This is pretty pointless as they always have the same shape. This caused me to perform 2 page table walks for every single memory access.

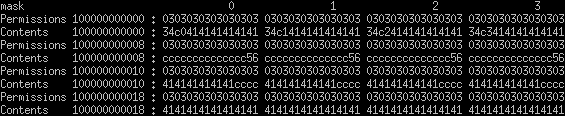

In the new model I interleave the memory and permissions for the VMs such that one walk will give me access to the permissions and memory contents. Further in memory the permissions come first followed by the contents. Since permissions are checked first this allows for the memory to be accessed linearally and potentially get a speedup by the hardware prefetchers.

When permissions and contents are laid out in a pretty format it looks something like:

Simplified to 4 lanes instead of 8

We can see every byte of contents has a byte of permissions and the permissions come first in memory. This image displays directly how the memory looks if you were to dump the MMU region for a page as qwords.

Uninitialized memory tracking

To track uninitialized memory I introduce a new permission bit called the RaW (read-after-write) bit. This bit indicates that memory is only readable after it has been written to. In allocator hooks or by manual application to regions of memory this bit can be set and the read bit cleared.

On all writes to memory the RaW it is unconditionally copied to the read bit. It’s done unconditionally because it’s cheaper to shift-and-or every time than have a conditional operation.

Simple as that, now memory marked as RaW and non-readable will become readable on writes! Just like all other permission bits this is byte-level. malloc()ing 8 bytes, writing one byte to it, and then reading all 8 bytes will cause an uninitialized memory fault!

Gage fuzzing

Okay there’s probably a name for this already but I call it ‘gage’ fuzzing (from gage blocks, precisely ground measurement references). It’s a precise fuzzing technique I use where I start without a snapshot at all, but rather just the code. In this case I load up a PE/ELF, mark all writable regions as read-after-write, and point PC to a function I want to fuzz. Further I set up the parameters to the function, and if one of the parameters happens to be a pointer to memory I don’t understand yet, I can mark the contents of the pointer to read-after-write as well.

As globals and parameters are used I get faults telling me that uninitialized memory was used. This allows me to reverse out the specific fields that the function operates on as needed. Since the memory is read-after-write, if the function writes to the memory prior to reading it then I don’t have to worry what that memory is at all.

This process is extremely time consuming, but it is basically dynamic-driven reversing/source auditing. You lazily reverse the things you need to, which forces you to understand small pieces at a time. While you build understanding of the things the function uses you ultimately learn the code and learn potential places to audit more or add things like guard bytes.

This is my go-to methodology for fuzzing extremely hard targets where every advantage is required. Further this works for fuzzing codebases which are not runnable, or you only have partial snapshots of. Works great for kernel fuzzing or firmware fuzzing when you don’t have a great way of getting a snapshot!

I mention ‘function’ in this case but there’s nothing restricting you from fuzzing a whole application with this model. Things without global state can be trivially fuzzed in their entirety with a model like this. Further, I’ve done things like call the init routine for a class/program and then jump to the parser when init returns to skip some of the manual processing.

Theory into practice

So we know the features and what we want in theory, however in practice things get a lot harder. We have to abide by the design decisions while maintaining some semblance of performance and support for edge cases in the JIT.

We’ve got a few things that could make this hard to JIT. First of all performance is going to be an issue, we need to find a way to minimize the frequency of page table walks as well as decrease the cost of a walk itself. Further we have to be able to support edge cases where VMs are disabled, pages are not present, and VMs are accessing different memory at the same time.

64-bit saves the day

Since now the vectorized emulator is 64-bit rather than 32-bit, we can hold pointers in lanes of the vector. This allows us to use the scatter and gather instructions during page table walks. However, while magical and fast at what they do, these scatter/gather instructions are much slower than their standard load/store counterparts.

Thus in the edge case where VMs are accessing different memory we are able to vectorize the page table walks. This means we’re able to perform 8 completely different page table walks at the same time. However in most cases VMs are accessing the same memory and thus it’s cheaper for us to check if we’re accessing different memory first, and either perform the same walk for all VMs (same address), or perform a vectorized page table walk with scatter/gather instructions.

In the case of differing addresses this vectorized page table walk is much faster than 8 separate walks and provides a huge advantage over the previous 32-bit model.

Handling non-present pages

Typically in most architectures there is a present bit used in the page tables to indicate that an entry is present. This really just allows them to map in the physical address NULL in page tables. Since we’re running as a user application using virtual addresses we cheat and just use the pointers for page table entries.

If an entry is NULL (64-bit zero), then we stop the walk and immediately deliver a fault. This means to perform the page table walk until the final page we simply read a page table entry, check if it’s zero, and go to the next level. No need to mask off permission/present bits. For the final level we have a dirty bit, and a few more bits which we must mask off. We’ll discuss these other bits later.

What is a page fault?

In the case of a non-present page in the page table, or a permission bit not being present for the corresponding operation we need a way to deliver a page fault. Since the VM is just effectively one big function, we’re able to set a register with a VM exit code and return out. This is an implementation detail but it’s important that a ret allows us to exit from the emulator at any time.

Further since it’s possible VMs could have different permissions or page tables, we report a caused_vmexit mask, which indicates which lanes of the vector were responsible for causing the exception. This allows us to record the results, disable the faulting VMs, and re-enter the emulator to continue running the remaining VMs.

Memory costs

Since we’re running vectorized code we interleave 8 VMs at the same time. Further there is a permission byte for every byte. We also have a minimum page size of 8-bytes. Meaning the smallest possible actual commit size for a page on a single hardware thread is 128 bytes. PAGE_SIZE (8 bytes) * NUM_VMS (8) * 2 (permission byte and content byte). This is important as a single 4096-byte x86 page is actually 64 KiB. Which is… quite large. The larger the page size the better the performance, but the higher memory usage.

Saving time and memory

We’ve discussed that the previous MMU model used was quite slow for startup and shutdown times. This mean it could take 30+ seconds to start the emulator, and another 30 seconds to exit the process. Even with a hard ctrl+c.

To remedy this, everything we do is lazy. When I say lazy I mean that we try to only ever create mappings, copies, and perform updates when absolutely required.

VMs have no memory to start off

When a VM launches it has zero memory in it’s MMU. This means creating a VM costs almost nothing (a few milliseconds). It creates an empty page table and that’s it.

So where does memory come from?

Since a VM starts off with no memory at all, it can’t possibly have the contents of the snapshot we are executing from. This is because only the metadata of the snapshot was processed. When the VM attempts to touch the first memory it uses (likely the memory containing the first instruction), it will raise an exception.

We’ve designed the MMU such that there is an ability to install an exception handler. This means that on an exception we can check if the input snapshot contained the memory we faulted on. If it did then we can read the memory from the snapshot and map it in. Then the VM can be resumed.

This has the awesome effect of only memory that is ever touched is brought in from disk. If you have a 100 terabyte memory snapshot but the fuzz case only touches 1 MiB of memory, you only ever actually read 1 MiB from disk (plus the metadata of the snapshot, eg. PE/ELF headers). This memory is pulled in based on the page granularity in use. Since this is configurable you can tweak it to your hearts desire.

Sharing memory / forking

Memory which is only ever read has no reason to be copied for every VM. Thus we need a mechanism for sharing read-only memory between VMs. Further memory is shared between all cores running in the same “IL session”, or group of VMs fuzzing the same code and target.

We accomplish this by using a forking model. A ‘master’ MMU is created and an exception handler is installed to handle faults (to lazily pull in memory contents). The master MMU is the template for all future VMs and is the state of memory upon a reset.

When a core comes up, a fork from this ‘master’ MMU is created. Once again this is lazy. The child has no memory mapped in and will fault in pages from the master when needed.

When a page is accessed for reading only by a child VM the page in the child is directly mapped to the master’s copy. However since this memory could theoretically have write-permissions at the byte level, we protect this memory by setting an aliased bit on the last level page table, next to the dirty bit. This gives us a mechanism to prevent a master’s memory from ever getting updated even if it’s writable.

To allow for writes to the VM we add another bit to the last level page tables, a cow, or copy-on-write, bit. This is always accompanied with the aliased bit, and instead of delivering a fault on a write-to-aliased-memory access, we create a copy of the master’s page and allow writes to that.

An example in aliased/CoWed memory access

This leads us to a pretty sophisticated potential model of fault patterns. Let’s walk through a common case example.

- An empty master MMU is created

- An exception handler is added to the master MMU that faults in pages from the disk on-demand

- A child is forked from the master

- A read occurs to a page in the child

- This causes an exception in the child as it has no memory

- The exception handler recognizes there’s a master for this child and goes to access the master’s memory for this page

- The master has no memory for this page and causes an exception

- The master’s exception handler handles loading the page from disk, creating an entry

- The master returns out with exception handled

- The child directly links in the master’s page as aliased

- Child returns with no exception

- Child then dispatches a write to the same memory

- The page is marked as aliased and thus cannot be written to

- A copy of the master’s page is made

- The permissions are checked in the page for write-access for all bytes being written to

- The write occurs in the child-owned page

- Success

While this is quite slow for the initial access, the child maintains it’s CoWed memory upon reset. This means that while the first few fuzz cases may be slow as memory is faulted in and copied, this cost eventually completely disappears as memory reaches a steady-state.

The overall result of this model is that memory only is ever read from disk if ever used, it then is only ever copied if it needs to be mutated. Memory which is only ever read is shared between all cores and greatly reduces cache pollution.

In theory a copy of all pages should be made for every NUMA node on the system to decrease latency in the case of a cache miss. This increases memory usage but increases performance.

All of this is done at page granularity which is configurable. Now you can see how big of an impact 8-byte pages can have as memory which may be writable (like a stack) but never is written to for a specific 8-byte region can be shared without extra memory cost.

This allows running 2048 4 GiB VMs with typically less than 200 MiB of memory usage as most fuzz cases touch a tiny amount of memory. Of course this will vary by target.

Deduplicated memory

Ha! You thought we were all done and ready to talk about performance? Not quite yet, we’ve got another trick up our sleeves!

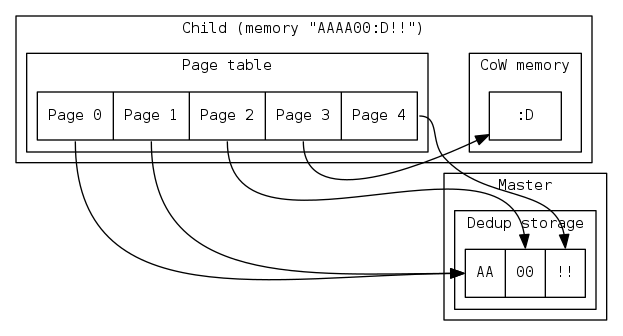

Since we’re already sharing memory and have support for aliased memory, we can take it one step further. When we add memory to the VM we can deduplicate it.

This might sound really complex, but the implementation is so simple that there’s almost no reason to not do it. Rather than directly creating memory in the the master, we can instead maintain a HashSet of pages and create aliased mappings to the entries in this set. When memory is added to a VM it is added to the deduplicated HashSet, which will create a new entry if it does not exist, or do nothing if it already exists. The page tables then directly reference the memory in this HashSet with the aliased bit set. Since pages contain the permissions this automatically handles creating different copies of the same memory with different permissions

Ta-da! We now will only create one read-only copy of each unique page. Say you have 1 MiB of read-writable zeros (would be 16 MiB when interleaved and with permissions), and are using 8-byte pages, you end up only ever creating one 8-byte page (128-byte actual backing) for all of this memory! As with other aliased memory, it can be cow memory and cloned if modified.

The gain from this is minimal in practice, but the code complexity increase given we already handle cow and aliased memory is so little that there’s really no reason to not do it. Since the Xeon Phi has no L3 cache, anything I can do to reduce cache pollution helps.

For example with a child with memory contents “AAAA00:D!!” where the “:D” was written in at offset 6.

Performance

Alright so we’ve talked about everything we implement in the MMU, but we haven’t talked at all about the JIT or performance.

There are two important aspects to performance:

- The JIT

- Injecting fuzz cases / allocating memory

The JIT performance being important should be obvious. Memory accesses are the most expensive things we can do in our emulator and are responsible from bringing our best case 2 trillion instructions/second benchmark to about 40-120 billion instructions/second in an actual codebase (old numbers, old MMU, 32-bit model). The faster we can make memory accesses, the closer we can get to this best-case performance number. This means we have a potential 50x speedup if we were to make memory accesses cost nothing.

Next we have the maybe-not-so-obvious performance-critical aspect. Getting fuzz cases into the VMs and handling dynamic allocations in the VMs. While this is pretty much never a problem in traditional fuzzers, on a small target I may be running between 2-5 million fuzz cases per second. Meaning I need to somehow perform 2-5 million changes to the MMU per second (typically 1024-or-so byte inputs).

Further the VM may dynamically allocate memory via malloc() which we hook to get byte-level allocation support and to track uninitialized memory. A VM might do this a few times a fuzz case, so this could result in potentially tens of millions of MMU modifications per second.

The JIT / IL

We’re not going to go into insane details as I’ve open sourced the actual JIT used in the MMU described by this blog. However we can hit on some of the high-level JIT and IL concepts.

When we’re running under the JIT there may be arbitrary VMs running (the VM-0-must-always-be-running restriction described in the intro has been lifted), as well as potential differing addresses that they are accessing.

Differing addresses

Since a vectorized page table walk is more expensive than a single page walk, we first always check whether or not the VMs that are active are accessing the same memory. If they’re accessing the same memory then we can extract the address from one of the VMs and perform a single scalar page walk. If they differ then we perform the more expensive vectorized walk (which is still a huge improvement from the 32-bit model of a different scalar walk for every differing address).

Since the only metadata we store in the page tables are the aliased, CoW, and dirty bits, the scalar page walk is safe to do for all VMs. If permissions differ between the VMs that’s fine as those bytes are stored in the page itself.

The part of the page walk that gets complex during a vectorized walk is updating the dirty bits. In a scalar walk it’s simple. If the dirty bit is not set and we’re performing a write, then we add to the dirty list and set the dirty bit. Otherwise we skip updating the dirty bit and dirty list. This prevents duplicate entries in the dirty list. Further we store the guest address and the translated address in the dirty list so we do not have to re-translate during a reset. If an exception occurs at any point during the walk, all VMs that are enabled are reported to have caused the exception.

We also perform the aliased memory check if and only if the dirty bit was not set. This aliased memory check is how we prevent writing to an aliased page. Since this check has a non-zero cost, and since dirty memory can never be aliased, we simply skip the check if the memory is already dirty. As it’s guaranteed to not be aliased if it’s dirty.

Vectorized translation

However in a vectorized walk it gets really tricky. First it’s possible that the different addresses fail translation at differing levels (during page table walks and during permission checks). Further they can have differing dirtiness which might require multiple entries to be added to the dirty list.

To handle translations failing at different points, we mask off VMs as they fail at various points. At the end of the translation we determine if any VM failed, and if it did we can report the failure correctly for all VM’s that failed at any point during the translation. This allows us to get a correct caused_vmexit mask from a single translation, rather than getting a partial report and getting more exceptions at a different translation stage on the next re-entry.

Vectorized dirty list updating

Further we have to handle dirty bits. I do this in a weird way right now and it might change over time. I’m trying to keep all possible JIT at parity with the interpreted implementation. The interpreted version is naive and simply performs the translations on all VMs in left-to-right order (see the JIT tests for this operation). This also maintains that no duplicates ever exist in the dirty lists.

To prevent duplicates in the dirty list we rely on the dirty bit in the page table, however when handling differing addresses we could potentially update the same address twice and create two dirty entries. The solution I made for this is to perform vectorized checks for the dirty bits, and if they’re already set we skip the expensive setting of the dirty bits. This is the fast path.

However in the slow path we store the addresses to the stack and individually update dirty bits and dirty entries for each lane. This prevents us from adding duplicates to the dirty list and keeps the JIT implementation at parity with the interpreter (thus allowing 1-to-1 checks for JIT correctness against the interpreter). Since we skip this slow path if the memory is already dirty, this probably won’t matter for performance. If it turns out to matter later on I might drop the no-duplicates-in-the-dirty-list restriction and vectorize updates to this list.

IL MMU routines

I’m going to have a whole blog on my IL, but it’s a simple SSA IL.

Memory accesses themselves are pretty fast in my vectorized model, however the translations are slow. To mitigate this I split up translations and read/write operations in my IL. Since page walks, dirty updates, and permission checks are done in my translate IL instruction, I’m able to reuse translations from previous locations in the IL graph which use the same IL expression as the address.

For example, a 4-byte translate for writing of rsp+0x50 occurs at the root block of a function. Now at future locations in the graph which read or write at the same location for 4-or-fewer bytes can reuse the translation. Since it’s an SSA the rsp+0x50 value is tied to a certain version of rsp, thus changes to rsp do not cause the wrong translation to be used. This effectively deletes the page walks for stack locals and other memory which is not dynamically indexed in the function. It’s kind of like having a TLB in the IL itself.

Since the initial translate was responsible for the permission checks and updates of things like the RaW bits and dirty bits, we never have to run these checks again in this case. This turns memory operations into simple loads and stores.

Since stores are supersets of loads and larger sizes are supersets of smaller sizes, I can use translations from slightly different sizes and accesses.

Since it’s possible a VM exit occurs and memory/permissions are changed, I must have invalidate these translations on VM exits. More specifically I can invalidate them only on VM entries where a page table modification was made since the last VM exit. This makes the invalidate case rare enough to not matter.

The performance numbers

These are the performance numbers (in cycles) for each type and size of operation. The translate times are the cost of walking the page tables and validating permissions, the access times are the cost of reading/writing to already translated memory. The benchmarks were done on a Xeon Phi 7210 on a single hardware thread. All times are in cycles for a translation and access times for all 8 lanes.

These are best-case translate/access times as it’s the same memory translated in a loop over and over causing the tables and memory in question to be present in L1 cache.

The divergent cases are ones where different addresses were supplied to each lane and force vectorized page walks.

Write: false | opsize: 1 | Diverge: false | Translate 37.8132 cycles | Access 10.5450 cycles

Write: false | opsize: 2 | Diverge: false | Translate 39.0831 cycles | Access 11.3500 cycles

Write: false | opsize: 4 | Diverge: false | Translate 39.7298 cycles | Access 10.6403 cycles

Write: false | opsize: 8 | Diverge: false | Translate 35.2704 cycles | Access 9.6881 cycles

Write: true | opsize: 1 | Diverge: false | Translate 44.9504 cycles | Access 16.6908 cycles

Write: true | opsize: 2 | Diverge: false | Translate 45.9377 cycles | Access 15.0110 cycles

Write: true | opsize: 4 | Diverge: false | Translate 44.8083 cycles | Access 16.0191 cycles

Write: true | opsize: 8 | Diverge: false | Translate 39.7565 cycles | Access 8.6500 cycles

Write: false | opsize: 1 | Diverge: true | Translate 140.2084 cycles | Access 16.6964 cycles

Write: false | opsize: 2 | Diverge: true | Translate 141.0708 cycles | Access 16.7114 cycles

Write: false | opsize: 4 | Diverge: true | Translate 140.0859 cycles | Access 16.6728 cycles

Write: false | opsize: 8 | Diverge: true | Translate 137.5321 cycles | Access 14.1959 cycles

Write: true | opsize: 1 | Diverge: true | Translate 158.5673 cycles | Access 22.9880 cycles

Write: true | opsize: 2 | Diverge: true | Translate 159.3837 cycles | Access 21.2704 cycles

Write: true | opsize: 4 | Diverge: true | Translate 156.8409 cycles | Access 22.9207 cycles

Write: true | opsize: 8 | Diverge: true | Translate 156.7783 cycles | Access 16.6400 cycles

Performance analysis

These numbers actually look really good. Just about 10 or so cycles for most accesses. The translations are much more expensive but with TLBs and caching the translations in the IL tree we should hopefully do these things rarely. The divergent translation times are about 3.5x more expensive than the scalar counterparts which is pretty impressive. 8 separate page walks at only 3.5x more cost than a single walk! That’s a big win for this new MMU!

TLBs (not implemented as of this writing)

Similar to the cached translations in the IL tree, I can have a TLB which caches a limited amount of arbitrary translations, just like an actual CPU or many other JITs. I currently plan on having TLB entries for each type of operation such that no permission checks are needed on read/write routines. However I could use a more typical TLB model where translations are cached (rather than permission checks and RaW updates), and then I would have to perform permission checks and RaW updates on all memory accesses (but not the translation phase).

I plan to just implement both models and benchmark them. The complexity of theorizing this performance difference is higher than just doing it and getting real measurements…

Fast injection/permission modifications

To support fast fuzz case injection and permission changes I have a few handwritten AVX-512 routines which are optimized for speed. These can then be tested against the naive reference implementation for correctness as there’s a much higher chance for mistakes.

I expose 3 different routines for this. A vectorized broadcast (writing the same memory to multiple VMs), a vectorized memset (applying the same byte to either memory contents or permissions), and a vectorized write-multiple.

Vectorized broadcast

This one is pretty simple. You supply an address in the VM, a payload, and a mask (deciding which VMs to actually write to). This will then write the same payload to all VMs which are enabled by the mask. This surprisingly doesn’t have a huge use case that I can think of yet.

Vectorized memset

Since permissions and memory are stored right next to each other this memset is written in a way that it can be used to update either permissions or contents. This takes in an address, a byte to broadcast, a bool indicating if it should write to permissions or contents, and a mask of VMs to broadcast to.

This routine is how permissions are updated in bulk. I can quickly update permissions on arbitrary sets of VMs in a vectorized manner. Further it can be used on contents to do things like handle zeroing of memory on a hooked call like malloc().

Vectorized write-multiple

This is how we get fuzz cases in. I take one address, a VM mask, and multiple inputs. I then inject those inputs to their corresponding VMs all at the same address. This allows me to write all my differing fuzz cases to the same location in memory very quickly. Since most fuzzing is writing an input to all VMs at the same location this should suffice for most cases. If I find I’m frequently writing multiple inputs to multiple different locations I’ll probably make another specialized routine.

Due to the complexities of handling partial reads from the input buffers in a vectorized way, this routine is restricted to writing 8-byte size aligned payloads to 8-byte aligned addresses. To get around this I just pad out my fuzz inputs to 8-byte boundaries.

Are these fast routines really needed?

For example the benchmarks for the Rust implementation for a page table of shape: [16, 16, 16, 13, 3]

Note that the benchmarks are a single hardware thread running on a Xeon Phi 7210

Empty SoftMMU created in 0.0000 seconds

1 MiB of deduped memory added in 0.1873 seconds

1024 byte chunks read per second 30115.5741

1024 byte chunks written per second 29243.0394

1024 byte chunks memset per second 29340.3969

1024 byte chunks permed per second 34971.7952

1024 byte chunks write multiple per second 6864.1243

And the AVX-512 handwritten implementation on the same machine and same shape:

Empty SoftMMU created in 0.0000 seconds

1 MiB of deduped memory added in 0.1878 seconds

1024 byte chunks read per second 30073.5090

1024 byte chunks written per second 770678.8377

1024 byte chunks memset per second 777488.8143

1024 byte chunks permed per second 780162.1310

1024 byte chunks write multiple per second 751352.4038

Effectively a 25x speedup for the same result!

With a larger page size ([16, 16, 16, 6, 10]) this number goes down as I can use the old translation longer and I spend less time translating pages:

Rust implementations:

Empty SoftMMU created in 0.0001 seconds

1 MiB of deduped memory added in 0.0829 seconds

1024 byte chunks read per second 30201.6634

1024 byte chunks written per second 31850.8188

1024 byte chunks memset per second 31818.1619

1024 byte chunks permed per second 34690.8332

1024 byte chunks write multiple per second 7345.5057

Hand-optimized implementations:

Empty SoftMMU created in 0.0001 seconds

1 MiB of deduped memory added in 0.0826 seconds

1024 byte chunks read per second 30168.3047

1024 byte chunks written per second 32993840.4624

1024 byte chunks memset per second 33131493.5139

1024 byte chunks permed per second 36606185.6217

1024 byte chunks write multiple per second 10775641.4470

In this case it’s over 1000x faster for some of the implementations! At this rate we can trivially get inputs in much faster than the underlying code possibly could run!

Future improvements/ideas

Currently a full 64-bit address space is emulated. Since nothing we emulate uses a full 64-bit address space this is overkill and increases the page table memory size and page table walk costs. In the future I plan to add support for partial address space support. For example if you only define the page table to handle 16-bit addresses, it will, optionally based on another constant, make sure addresses are sign-extended or zero-extended from these 16-bit addresses. By supporting both sign-extended and zero-extended addresses we should be able to model all architecture’s specific behaviors. This means if running a 32-bit application in our 64-bit JIT we could use a 32-bit address space and decrease the cost of the MMU.

I could add more fast-injection routines as needed.

I may move permission checks to loads/stores rather than translation IL operations, to allow reuse of TLB entries for the same page but differing offsets/operations.