Miniblog: How conditional branches work in Vectorized Emulation

Follow me at @gamozolabs on Twitter if you want notifications when new blogs come up. I also do random one-off posts for cool data that doesn’t warrant an entire blog!

Let me know if you like this mini-blog format! It takes a lot less time than a whole blog, but I think will still have interesting content!

Prereqs

You should probably read the Introduction to Vectorized Emulation blog!

Or perhaps watch the talk I gave at RECON 2019

Summary

I spent this weekend working on a JIT for my IL (FalkIL, or fail). I thought this would be a cool opportunity to make a mini-blog describing how I currently handle conditional branches in vectorized emulation.

This is one of the most complex parts of vectorized emulation, and has a lot of depth. But today we’re going to go into a simple merging example. What I call the “auto-merge”. I call it an auto-merge because it doesn’t require any static analysis of potential merging points. The instructions that get emit simply allow for auto re-merging of divergent VMs. It’s really simple, but pretty nifty. We have to perform this logic on every branch.

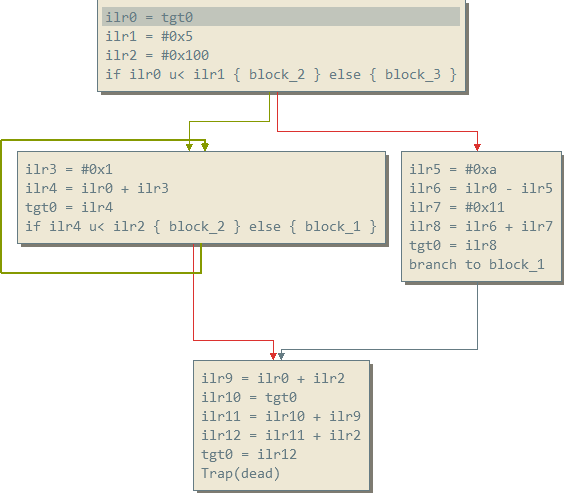

FalkIL Example

Here’s an example of what FalkIL looks like:

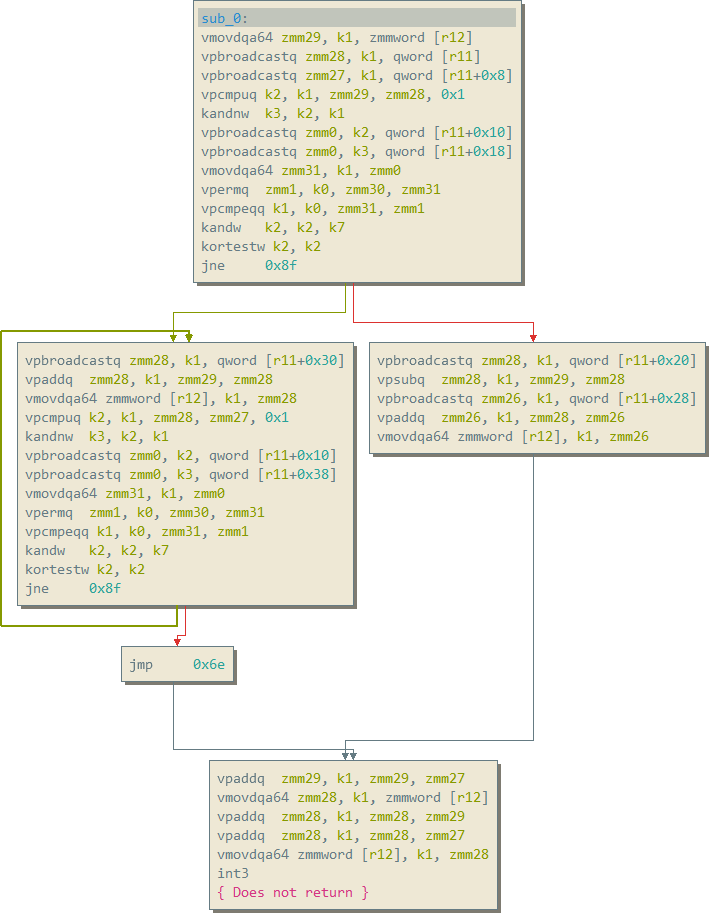

JIT

Here’s what the JIT for the above IL example looks like:

Ooof… that exploded a bit. Let’s dive in!

JIT Calling Convention

Before we can go into what the JIT is doing, we have to understand the calling convention we use. It’s important to note that this calling convention is custom, and follows no standard convention.

Kmask Registers

Kmask registers are the bitmasks provided to us in hardware to mask off certain operations. Since we’re always executing instructions even if some VMs have been disabled, we must always honor using kmasks.

Intel provides us with 8 kmask registers. k0 through k7. k0 is hardcoded in hardware to all ones (no masking). Thus, we’re not able to use this for general purpose masking.

Online VM mask

Since at any given time we might be performing operations with VMs disabled, we need to have one kmask register always dedicated to holding the mask of VMs that are actively running. Since k1 is the first general purpose kmask we can use, that’s exactly what we pick. Any bit which is clear in k1 (VM is disabled), must not have its state modified. Thus you’ll see k1 is used as a merging mask for almost every single vectorized operation we do.

By using the k1 mask in every instruction, we preseve the lanes of vector registers which are disabled. This provides near-zero-cost preservation of disabled VM states, such that we don’t have to save/restore massive ZMM registers during divergence.

This mask must also be honored during scalar code that emulates complex vectorized operations (for example divs, which have no vectorized instruction).

“Following” VM mask

At some points during emulation we run into situations where VMs have to get disabled. For example, some VMs might take a true branch, and others might take the false (or “else”) side of a branch. In this case we need to make a decision (very quickly) about which VM to follow. To do this, we have a VM which we mark as the “following” VM. We store this “following” VM mask in k7. This always contains a single bit, and it’s the bit of the VM which we will always follow when we have to make divergence decisions.

The VM we are “following” must always be active, and thus (k7 & k1) != 0 must always be true! This k7 mask only has to be updated when we enter the JIT, thus the computation of which VM to “follow” may be complex as it will not be a common expense. While the JIT is executing, this k7 mask will never have to be updated unless the VM we are following causes a fault (at which point a new VM to follow will be computed).

Kmask Register Summary

Here’s the complete state of kmask register allocation during JIT

K0 - Hardcoded in hardware to all ones

K1 - Bitmask indicating "active/online" VMs

K2-K6 - Scratch kmask registers

K7 - "Following" VM mask

ZMM registers

The 512-bit ZMM registers are where we store most of our active contextual data. There are only 2 special case ZMM registers which we reserve.

“Following” VM index vector

Following in the same suit of the “Following VM mask”, mentioned above, we also store the index for the “following” VM in all 8 64-bit lanes of zmm30. This is needed to make decisions about which VM to follow. At certain points we will need to see which VM’s “agree with” the VM we are following, and thus we need a way to quickly broadcast out the following VMs values to all components of a vector.

By holding the index (effectively the bit index of the following VM mask) in all lanes of the zmm30 vector, we can perform a single vpermq instruction to broadcast the following VM’s value to all lanes in a vector.

Similar to the VM mask, this only needs to be computed when the JIT is entered and when faults occur. This means this can be a more expensive operation to fill this register up, as it stays the same for the entirity of a JIT execution (until a JIT/VM exit).

Why this is important

Lets say:

zmm31 contains [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]

zmm30 contains [3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3]

The CPU then executes vpermq zmm0, zmm30, zmm31

zmm0 now contains [13, 13, 13, 13, 13, 13, 13, 13]… the 3rd VM’s value in zmm31 broadcast to all lanes of zmm0

Effectively vpermq uses the indicies in its second operand to select values from the third operand.

“Desired target” vector

We allocate one other ZMM register (zmm31) to hold the block identifiers for where each lane “wants” to execute. What this means is that when divergence occurs, zmm31 will have the corresponding lane updated to where the VM that diverged “wanted” to go. VMs which were disabled thus can be analyzed to see where they “wanted” to go, but instead they got disabled :(

ZMM Register Summary

Here’s the complete state of ZMM register allocation during JIT

Zmm0-Zmm3 - Scratch registers for internal JIT use

Zmm4-Zmm29 - Used for IL register allocation

Zmm30 - Index of the VM we are following broadcast to all 8 quadwords

Zmm31 - Branch targets for each VM, indicates where all VMs want to execute

General purpose registers

These are fairly simple. It’s a lot more complex when we talk about memory accesses and such, but we already talked about that in the MMU blog!

When ignoring the MMU, there are only 2 GPRs that we have a special use for…

Constant storage database

On the Knights Landing Xeon Phi (the CPU I develop vectorized emulation for), there is a huge bottleneck on the front-end and instruction decode. This means that loading a constant into a vector register by loading it into a GPR mov, then moving it into the lowest-order lane of a vector vmovq, and then broadcasting it vpbroadcastq, is actually a lot more expensive than just loading that value from memory.

To enable this, we need a database which just holds constants. During the JIT, constants are allocated from this table (just appending to a list, while deduping shared constants). This table is then pointed to by r11 during JIT. During the JIT we can load a constant into all active lanes of a VM by doing a single vpbroadcastq zmm, kmask, qword [r11+OFFSET] instruction.

While this might not be ideal for normal Xeon processors, this is actually something that I have benchmarked, and on the Xeon Phi, it’s much faster to use the constant storage database.

Target registers

At the end of the day we’re emulating some other architecture. We hold all target architecture registers in memory pointed to by r12. It’s that simple. Most of the time we hold these in IL registers and thus aren’t incurring the cost of accessing memory.

GPR summary

r11 - Points to constant storage database (big vector of quadword constants)

r12 - Points to target architecture registers

Phew

Okay, now we know what register states look like when executing in JIT!

Conditional branches

Now we can get to the meat of this mini-blog! How conditional branches work using auto-merging! We’re going to go through instruction-by-instruction from the JIT graph we showed above.

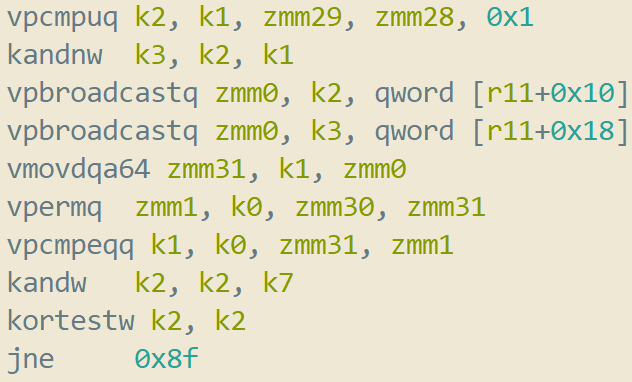

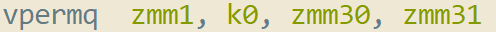

Here’s the specific code in question for a conditional branch:

Well that looks awfully complex… but it’s really not. It’s quite magical!

The comparison

First, the comparision is performed on all lanes. Remember, ZMM registers hold 8 separate 64-bit values. We perform a 64-bit unsigned comparison on all 8 components, and store the results into k2. This means that k2 will hold a bitmask with the “true” results set to 1, and the “false” results set to 0. We also use a kmask k1 here, which means we only perform the comparison on VMs which are currently active. As a result of this instruction, k2 has the corresponding bits set to 1 for VMs which were actively executing at the time, and also resulted in a “true” value from their comparisons.

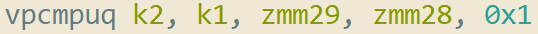

In this case the 0x1 immediate to the vpcmpuq instruction indicates that this is a “less than” comparison.

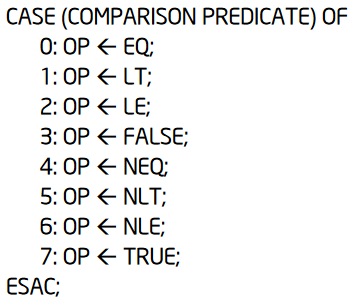

vpcmpq/vpcmpuq immediate

Note that the immediate value provided to vpcmpq and the unsigned variant vpcmpuq determines the type of the comparison:

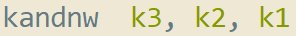

The comparison inversion

Next, we invert the comparison operation to get the bits set for active VMs which want to go to the “false” path. This instruction is pretty neat.

kandnw performs a bitwise negation of the second operand, and then ands with the third operand. This then is stored into the first operand. Since we have k2 as the second operand (the result of the comparison) this gets negated. This then gets anded with k1 (the third operand) to mask off VMs which are not actively executing. The result is that k3 now contains the inverted result from the comparison, but we keep “offline” VMs still masked off.

In C/C++ this is simply: k3 = (~k2) & k1

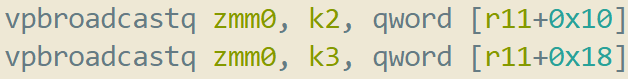

The branch target vector

Now we start constructing zmm0… this is going to hold the “labels” for the targets each active lane wants to go to. Think of these “labels” as just a unique identifier for the target block they are branching to. In this case we use the constant storage database (pointed to by r11) to load up the target labels. We first load the “true target” labels into zmm0 by using the k2 kmask, the “true” kmask. After this, we merge the “false target” labels into zmm0 using k3, the “false/inverted” kmask.

After these 2 instructions execute, zmm0 now holds the target “labels” based on their corresponding comparison results. zmm0 now tells us where the currently executing VMs “want to” branch to.

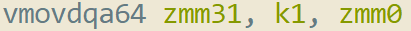

The merge into master

Now we merge the target branches for the active VMs which were just computed (zmm0), into the master target register (zmm31). Since VMs can be disabled via divergence, zmm31 holds the “master” copy of where all VMs want to go (including ones which have been masked off and are “waiting” to execute a certain target).

zmm31 now holds the target labels for every single lane with the updated results of this comparison!

Broadcasting the target

Now that we have zmm31 containing all of the branch targets, we now have to pick the one we are going to follow. To do this, we want a vector which contains the broadcasted target label of the VM we are following. As mentioned in the JIT calling convention section, zmm30 contains the index of the VM we are following in all 8 lanes.

Example

Lets say for example we are following VM #4 (zero-indexed).

zmm30 contains [4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4]

zmm31 contains [block_0, block_0, block_1, block_1, block_2, block_2, block_2, block_2]

After the vpermq instruction we now have zmm1 containing [block_2, block_2, block_2, block_2, block_2, block_2, block_2, block_2].

Effectively, zmm1 will contain the block label for the target that the VM we are following is going to go to. This is ultimately the block we will be jumping to!

Auto-merging

This is where the magic happens. zmm31 contains where all the VMs “want to execute”, and zmm1 from the above instruction contains where we are actually going to execute. Thus, we compute a new k1 (active VM kmask) based on equality between zmm31 and zmm1.

Or in more simple terms… if a VM that was previously disabled was waiting to execute the block we’re about to go execute… bring it back online!

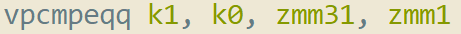

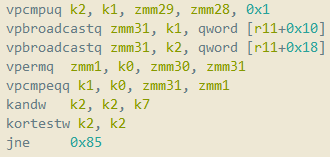

Doin’ the branch

Now we’re at the end. k2 still holds the true targets. We and this with k7 (the “following” VM mask) to figure out if the VM we are following is going to take the branch or not.

We then need to make this result “actionable” by getting it into the eflags x86 register such that we can conditionally branch. This is done with a simple kortestw instruction of k2 with itself. This will cause the zero flag to get set in eflags if k2 is equal to zero.

Once this is done, we can do a jnz instruction (same as jne), causing us to jump to the true target path if the k2 value is non-zero (if the VM we’re following is taking the true path). Otherwise we fall through to the “false” path (or potentially branch to it if it’s not directly following this block).

Update

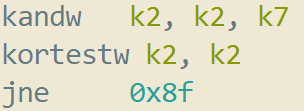

After a little nap, I realized that I could save 2 instructions during the conditional branch. I knew something was a little off as I’ve written similar code before and I never needed an inverse mask.

Here we’ll note that we removed 2 instructions. We no longer compute the inverse mask. Instead, we initially store the false target block labels into zmm31 using the online mask (k1). This temporarly marks that “all online VMs want to take the false target”. Then, using the k2 mask (true targets), merge over zmm31 with the true target block labels.

Simple! We remove the inverse mask computation kandnw, and the use of the zmm0 temporary and merge directly into zmm31. But the effect is exactly the same as the previous version.

Not quite sure why I thought the inverse mask was needed, but it goes to show that a little bit of rest goes a long way!

Due to instruction decode pressure on the Xeon Phi (2 instructions decoded per cycle), this change is a minimum 1 cycle improvement. Further, it’s a reduction of 8 bytes of code per conditional branch, which reduces L1i pressure. This is likely in the single digit percentages for overall JIT speedup, as conditional branches are everywhere!

Fin

And that’s it! That’s currently how I handle auto-merging during conditional branches in vectorized emulation as of today! This code is often changed and this is probably not its final form. There might be a simpler way to achieve this (fewer instructions, or lower latency instructions)… but progress always happens over time :)

It’s important to note that this auto-merging isn’t perfect, and most cases will result in VMs hanging, but this is an extremely low cost way to bring VMs online dynamically in even the tightest loops. More macro-scale merging can be done with smarter static-analysis and control flow decisions.

I hope this was a fun read! Let me know if you want more of these mini-blogs.